As the world waits for the Vatican’s conclave to select a new pope to lead 1.2 billion Roman Catholics, and the church’s sex abuse scandals dominate discourse on the incoming pontiff’s priorities, another decidedly worldly issue is also poised to take an immediate toll on the new Holy Father: money.

The public and private woes of the Vatican bank, long shrouded in secrets and whispers, might well prove to be just as challenging, if not as draining, as the lurid, faith-shaking damage of the clergy abuse scandal.

With a two-year probe by Italian authorities into money laundering, poor transparency, inadequate adherence to standards for guarding against criminal and terrorist financing, and questions over sudden changes in its leadership, the bank represents another crisis of morals, legalities and perception.

The importance of the Vatican bank in Pope Benedict XVI’s grand vision can be assumed from the urgency it held with the outgoing pontiff: among the last official acts before his shock retirement was overhauling financial leadership and church oversight.

On Feb. 15, Benedict XVI approved the appointment of Ernst von Freyberg as the new president of the supervisory board of the Institute for Works of Religion, the church agency widely known as the Vatican bank.

The appointment of the German lawyer and businessman came after assessing “a number of candidates of professional and moral excellence,” the Vatican said in a statement.

“The Holy Father has closely followed the entire selection process … and he has expressed his full consent to the choice made by the Commission of Cardinals.”

While the appointment drew immediate criticism over the involvement of Mr. von Freyberg’s Blohm+Voss, an industrial group, in manufacturing German warships, including during the Nazi era, it also raised eyebrows for its timing. Putting money under the baton of a German is not out of step with European policy these days, but for an institution already rife with conspiracy theories the sudden shuffle could not go unnoticed.

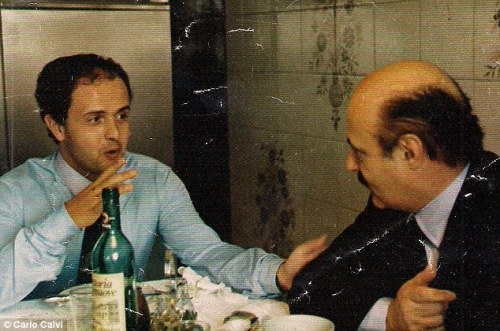

“[Benedict’s] decision to retire was so unprecedented, you would think that he would have other things on his mind than replacing the head of the Vatican bank,” said Carlo Calvi, son of Roberto Calvi, who was known as “God’s Banker” because of his close ties to the Vatican before his outlandish death more than 30 years ago.

“However, I am more surprised by the sackings — the people who were let go — rather than the appointments,” he said.

Ettore Gotti Tedeschi was chairman of the Vatican bank until he was pushed out in May with a withering assessment of not being up for the job. He had been trying to get the Vatican onto the international banking “white list” of virtuous countries.

Then, on Feb. 22, Monsignor Ettore Balestrero, a key church official pushing for better regulation and controls on the Vatican bank, was suddenly transferred from Rome to Colombia.

That transfer followed the moving of Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, who was credited with turning a deficit for the Vatican into a large surplus through greater accountability and controls, from the Vatican to the United States.

One of the leaked documents in the “Vatileaks” scandal was a letter from Archbishop Vigano to Pope Benedict begging he remain in Rome to continue his financial crusade. The Pope was unmoved.

The transfers suggest change is not always welcome.

“Change under the new pope will be easier said than done because they make money on this, it is a source of income that has been used for a lot of purposes,” said Mr. Calvi. To address the problems, “They need, essentially, to do a very drastic reform that would almost certainly mean foregoing a considerable source of revenue.”

The Vatican bank has not always shown such virtuous strength, as Mr. Calvi knows better than most. Few outside the Vatican’s inner circle eye church finance as closely as Mr. Calvi, who now lives in Montreal.

Watching the Vatican bank has consumed Mr. Calvi’s adult life and the Calvi name almost consumed the Vatican bank.

His father was chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, an Italian Catholic bank closely linked to the Vatican.

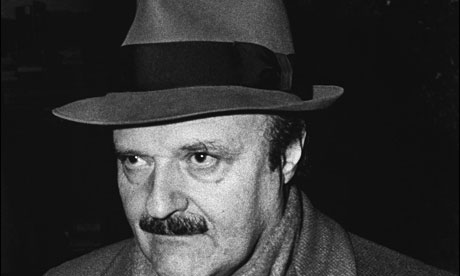

The shadowy operations of Vatican finance forced its way into the public’s consciousness when Roberto Calvi was found dead, just as the scandalous operation of church finance was being revealed amid the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano, Italy’s largest private bank, with $1-billion missing.

Since then, his unsolved death, first declared a suicide, then reclassified as a murder, and the cast of powerful figures and secretive organizations linked to it — from the Mafia and the Masonic lodge P2 to the powerful conservative Catholic organization Opus Dei and the Vatican itself — make it one of modern history’s enduring mysteries, Europe’s equal to the Jimmy Hoffa disappearance.

The case was also said to be linked to landmark Cold War politics, with claims Banco Ambrosiano was used by those close to John Paul II, the Polish pope, to fund the anti-Communist Solidarity movement in Poland and by those close to U.S. president Ronald Reagan to fund the Contra rebels of Central America.

The raw puzzle and quirks of Mr. Calvi’s death compel conspiracy theories and befuddlement, with small details that seem to mean much, but with no answer to exactly what.

The banker’s body was found hanging under Blackfriars Bridge, his feet dangling in the River Thames in the heart of London, on June 18, 1982; he wore two pairs of underwear, had five bricks in his pockets, about $14,00-worth of three different currencies and the business card of a Mafia figure.

It was a death shouting in the symbolic language of Italy’s underworld.

“I am more of the idea that there are theatrical elements and not necessarily symbolic aspects to it,” said his son. “Hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars were involved — if that is not a motive for murder, I don’t know what is.”

After all, any Catholic cleric would know: Radix malorum est cupiditas, the Latin Biblical quotation meaning greed is the root of evil.

The very notion of a church bank speaks to the awkward interface between the spiritual and temporal, represented by the pope being both leader of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City state.

Unlike many Vatican institutions, the Vatican bank is not of antique origin, having been formed in 1942 by Pius XII, although it had older antecedents. Its purpose is to protect and administer the property and funds intended for the church’s works.

Related

- Pope election date set for March 12

- Analysis: Spiraling scandal reveals Machiavellian manoeuvering within the Vatican

- European report rips into Vatican bank for lack of oversight, transparency

- As Pope Benedict departs, intrigue of who will succeed him heats up

- Pope’s resignation tied to blackmailed gay-lobby within the Vatican: Italian newspaper

Unlike true national central banks, it does not set monetary policy or involve itself in currency maintenance, as the Vatican uses the euro. Also unlike most banks, its surplus or profit is supposed to go toward religion or charity.

As it is not a true central bank, and with the Vatican not a full member of the European Union, its relationship with strict regulation has been more nebulous and its ends of religion or charity have, likewise, not always been clear.

“One would be surprised at the acceptance of risky relationships and risky behaviour for an organization like the Vatican. But, objectively, I’ve seen it. It is hard to understand, but it is true,” said Mr. Calvi.

“In many cases, they seem to have little judgment in terms of the arrangements they get themselves into.”

In the fallout of the Banco Ambrosiano scandal, though it claimed no wrongdoing, the Vatican bank paid $250-million to Ambrosiano’s creditors.

Since then, its regulatory framework has still not caught up to modern standards, especially in the post-9/11 world.

In 2010, Rome magistrates froze ¤23-million ($31-million) the Vatican bank held in an Italian bank. The Vatican said its bank was merely transferring its own funds between its own accounts in Italy and Germany. The money was released in June 2011, but an investigation continues.

In July, a European anti-money laundering committee said the Vatican bank failed to meet all its standards on fighting money laundering, tax evasion and other financial crimes.

The report by Moneyval, a monitoring committee of the 47-nation Council of Europe, found the Vatican passed nine of 16 “key and core” aspects of its financial dealings. The head of the Vatican delegation to the Moneyval committee was Msgr. Balestrero.

Msgr. Balestrero said the report was a call for the Vatican to push forward with “efforts to marry moral commitments to technical excellence” to prove “the Holy See’s and Vatican City state’s desire to be a reliable partner in the international community.”

Seven months later, he was reassigned to South America.

“The Moneyval report was one of the rare bits of good news for the Vatican last year. Balestrero was the one who dealt with Moneyval and they send him to Colombia. That doesn’t sound like the way to reward someone,” said Mr. Calvi.

This week, the widely read Italian Catholic weekly Famiglia Cristiana, which is distributed free in Italian parishes on Sundays, carried an article calling for the bank to be closed on the grounds the pontificate should not have direct links to the world of finance.

It argued there are plenty of ethically minded commercial banks in Italy and elsewhere that could be trusted to manage the Holy See’s assets.

In January, René Bruelhart, the new director of the Vatican’s Financial Information Authority, said the church was on the right track.

“Considering the particular nature of the Vatican City state, adequate measures have been adopted for vigilance, prevention, and fighting money laundering and financing terrorism,” he told the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera.

How much further the Vatican bank will go and how quickly it can get there, under both the new chairman and a new pope, is being anxiously watched by the world’s financial community. And by Mr. Calvi.

National Post, with files from news services